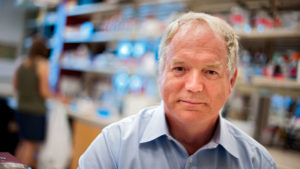

Photo : Michael Holly; ©University of Alberta

As the world continues to battle the COVID-19 pandemic, remarkable medical breakthroughs defeating other deadly diseases sometimes get lost. This is the story of hepatitis C. Today we celebrate historic good news from a Canadian university and a decisive Canada-U.S. medical victory.

On October 5, 2020, esteemed Edmonton-based University of Alberta virologist Michael Houghton was awarded the 2020 Nobel Peace Prize in Physiology or Medicine for discovering and understanding the insidious hepatitis C virus. Some 400,000 people globally die each year from complications caused by the virus, long viewed as an “incurable” disease. Patients previously treated with injected interferon-based drugs offering only limited efficacy suffered negative side effects.

Thanks to the work of Michael Houghton and his co-discoverers, Americans Harvey J. Alter and Charles M. Rice, most patients can now take a pill once a day for two or three months and rid themselves forever of this once intractable disease, making hepatitis C the first chronic viral illness that can now be cured. And a preventative vaccine currently under development at the University of Alberta and in the late pre-clinical stage of testing may not be far behind. Completely eradicating hepatitis C from the planet is now a goal within reach.

Dr. Houghton’s humility and grace in the face of his historic, life-saving accomplishments are remarkable. He has been a mentor and inspiration to many trainees in the complex field of virology. The man once turned down another prestigious scientific prize because his co-discoverers were not included. Even more than the prestigious recognition of his 2020 Nobel Prize, he said, “what counts for me even more is that we’ve been able to prevent millions of infections that otherwise would have occurred around the world …”.

It will come as no surprise that Houghton recently mobilized his hepatitis C lab to pursue a COVID-19 vaccine. The challenge is in good hands; Michael Houghton had also created a successful vaccine for the SARS-CoV-1 virus back in 2004, but, says the University of Alberta, “it was never needed” as the SARS outbreak was effectively contained in the end. Of COVID, Houghton says: “As terrible as it is and as tragic as it is – it’s actually created a new paradigm for developing vaccines. COVID-19 has moved the bar on the speed of research and understanding of what it takes to tackle viral illness. It’s showing us how fast we can develop [vaccines] when the will is there.”

University of Alberta President Bill Flanagan is thrilled that Houghton’s work on the Edmonton campus has received worldwide recognition. Houghton’s presence on this Canadian campus is further powerful testimony to the excellence of Canadian academic institutions and the world-class caliber of researchers and students that head north of the border. In fact, the University of Alberta hosts 8 Fulbright Canada Research Chairs for American scholars, the most chair positions out of any Canadian university.

Houghton and his team’s breakthroughs at the University’s Li Ka Shing Institute of Virology shine a light on what can be achieved when people rally around a shared vision. The 2020 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine is a resounding Canada-U.S. success story, showing what can (and did) happen when world-class virologists, an outstanding Canadian university, and funding support from the Government of Alberta and the non-profit sector all came together to defeat a killer disease.

October 5 was a great day for Canada and the University of Alberta. We’re staying tuned for more.