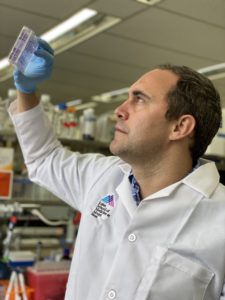

His Twitter name says it all: @VirusNinja.

Dr. Benjamin tenOever’s interest in virology goes back to his days at McGill University, but his interest in science stems from his early childhood.

His parents immigrated to Canada from the Netherlands following a wave of Dutch farmers recruited by the Canadian government to settle in Smithville, Ontario and introduce dairy farming to the area. His father came to serve as the town veterinarian.

With a population of around 5000, Smithville sits on top of an ancient shoreline nestled between Niagara Falls and Hamilton. Dr. tenOever describes the town of his childhood as being very conservative and old-fashioned, with everything revolving around a Dutch denomination of Christianity called Christian Reformed.

If Sundays were for church, Saturdays were for joining his father as he drove his truck from farm to farm to treat cows.

“I saw some crazy stuff. I had my hand on the beating heart of a one-ton cow at 7 years old. Those experiences definitely sparked my interest in science.”

As much as he appreciated the peculiarities of his upbringing, he jumped on opportunities to leave his Smithville bubble. After eleventh grade, he went on a student exchange trip to Tasmania, trading one tiny town for another, only on the other side of the world. The next summer, he went on a Christian mission trip to Malawi. There, he would meet the woman who would become his wife, but only after a decade-long pen-pal romance— proving perhaps that the old-fashioned ways of Smithville had rubbed off on him a little.

With plans to become a physician, Dr. tenOever headed to McGill University in Montreal for pre-medical studies. But when he took an elective microbiology class taught by a professor who clearly had an infectious passion for viruses, he was immediately hooked.

After that, he took every microbiology class he could. During his last year of undergraduate studies, he convinced a faculty member to sponsor an independent project to study hantaviruses in the rodent population in Montreal—for which he set up mouse traps around the university campus, at his own house, and in nearby Montreal parks.

“I was essentially the McGill exterminator, unaware that what I was doing was really wrong. This type of research required a lot of permissions that I didn’t have and safety protocols that I didn’t know.”

Ultimately, the project was shut down by the government biohazard safety committee to which he had applied to get the necessary permissions. And although he never did find the virus, the McGill biology department still gave him his independent study credit, and his unconventional approach to microbiology continued unabated from there.

While most microbiologists study one specific virus and how it replicates— Dr. tenOever was more interested in how cells recognize that they are infected by viruses. This would be the focus of his PhD research at McGill, which led him to one of his biggest findings: the discovery of virus-activated kinases, a component responsible for launching an anti-viral program in cells.

“All we knew when I started my PhD was that every cell that gets infected has two major jobs: a “call to arms” mediated by a protein family called interferons, which sends out a signal to other cells to fortify their defenses, and a “call for reinforcements” which releases different protein messengers that diffuse away from the site of infection, leaving a trail that is used by the immune system to get to the site of infection so they can properly mount an immune response,” he said. “But how cells knew they were infected by a virus was completely a black box. My research led to the discovery of a major cell component that was activated by viruses to orchestrate this antiviral process.”

This discovery was enough for Dr. tenOever to complete his PhD and pursue his postdoc at Harvard University. Rather than diversifying his research, as scientists are often encouraged to do, he wanted to see his discovery all the way through—and began studying virus-activated kinases in mice.

In three years, he completed his post-doc and at 29 years old, he was already on the job market looking to start his own lab. He came to Manhattan to join the Mount Sinai Department of Microbiology, a microcosm of New York City’s dynamism and diversity.

For the first time in his career he was surrounded by virologists. “I didn’t want to study the basic virology of a specific virus, I wanted to know how all viruses interact with the cells’ defenses. Being in a department full of virologists was helpful as I had all the tools to study different viruses in any way that I wanted— and this is when I really started to diversify and move in all sorts of directions.”

Dr. tenOever’s work evolved into building viruses— essentially breaking viruses into individual pieces and rebuilding them, not as viruses but as therapeutics, vaccines, and even cancer treatments. This work would earn him a Presidential Award in 2009. His lab was also awarded a Department of Defense contract to study a universal flu therapeutic, requiring his lab to have a Level 3 biosafety designation (BSL3), which is very difficult to obtain in the United States. That became crucial in the scramble to study SARS-CoV-2, or COVID-19, which can only be studied in BSL3 labs.

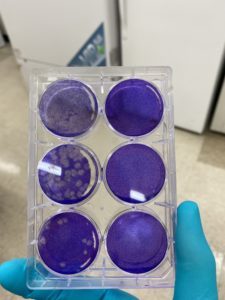

As the threat of COVID-19 became clear, his lab was able to quickly pivot to become entirely focused on studying the coronavirus. In addition to looking at how it affects different parts of the body, the lab was given a second contract with the Department of Defense to study how Federal Drug Administration (FDA) approved drugs can be repurposed to inhibit COVID-19 and serve as a treatment while the world waits for a vaccine. And while many of them do a very good job at inhibiting the virus in cell culture dishes, the key will be to find those that can decrease the effects of the virus without too many side effects.

Just last week, Dr. tenOever’s lab found that one promising FDA-approved compound could reduce the virus by 50% and even block transmission in hamsters. Another has shown that it could potentially eliminate the virus from the lungs, and downgrade the virus’ severity to nothing more than a common cold.

These findings make this Canadian microbiologist from a small town in Ontario, a.k.a. the Virus Ninja, on the verge of discovering a COVID-19 treatment that could be game-changing for the world.

After months of grueling work in the lab, and a lot of time spent away from his wife and two young daughters as the pandemic engulfed New York, Dr. tenOever could not hide his excitement and optimism that the city he loves would come back stronger than ever.

“This is as cutting edge as it gets, so stay tuned”.

Related Posts:

- Reflections from the Epicenter: a Canadian Doctor Describes Being on the Frontlines of the COVID-19 Outbreak

- COVID-19 Across the Border: Teaming Up on Treatments, Trials and Tracking – Not to Mention Vaccines

- Canada Supports Research into COVID-19 on Both Sides of Border

- COVID-19: Information for Canadians in the U.S.